Osteoporosis, Osteopenia & Bone Health

Bone is a complex tissue and its strength depends on genetics, how it grew during puberty, nutrient intake, exercise levels, and hormone levels throughout life. Women reach peak bone strength in their early thirties and often sharply lose bone density starting during the menopausal transition and continuing throughout the rest of their lives.

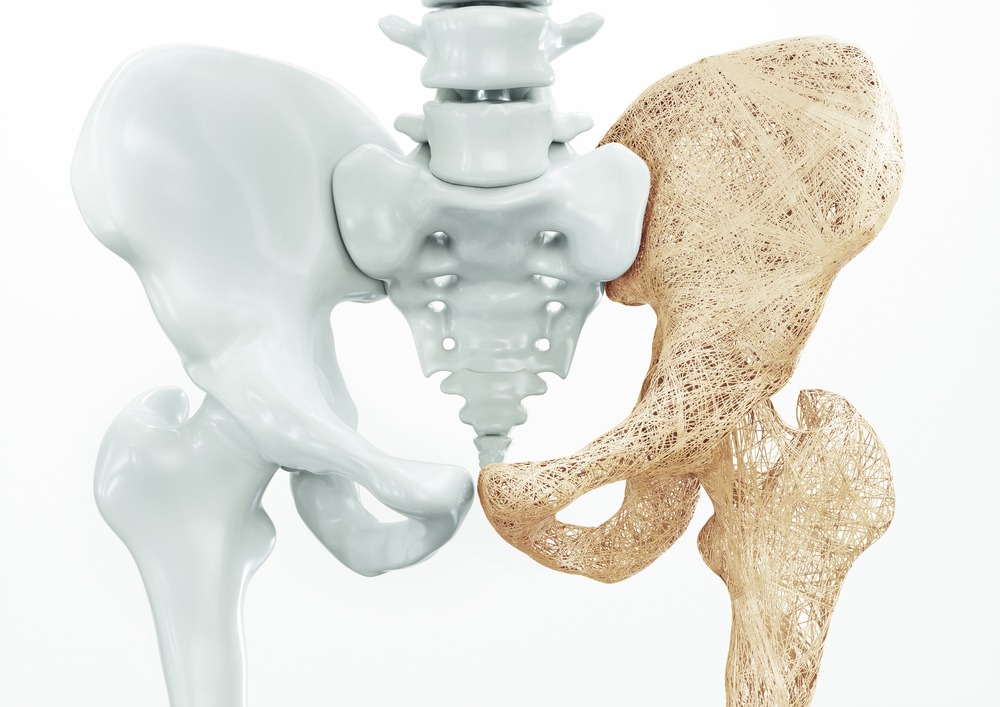

Osteoporosis is a skeletal disease which is characterized by low bone mineral mass and deterioration of bone tissue. Bone, as a living tissue, is continually replacing itself with new cells. In the case of osteoporosis and osteopenia, the creation of these new bone cells does not match the rate of aging and dying of old bone cells. This can lead to weakened bones and increased risk of fracture from low impact trauma. It is a “silent” disease that often shows up only after a bad bone fracture in mid- to- late life.

Osteopenia is a condition of low bone mass and if left unmanaged, will become osteoporosis. In the event of a bone fracture from a low-impact injury or loss of height, notify a care provider and request a bone density test.

Osteoporosis Risk Factors

Osteoporosis is not a direct symptom of the menopausal transition. However the reduction of estrogen and increase in follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) during the menopausal transition can make osteopenia and osteoporosis worse. Post-menopausal women, and white and Asian women are at particular risk.

Factors that increase risk for osteoporosis:

- Family history of broken bones or osteoporosis, which has a strong genetic influence

- Prior bone break from a low impact fall, indicating you may already have low bone density

- Early menopause or ovary removal before perimenopause

- Inadequate calcium and/or vitamin D in diet

- Physical inactivity

- Smoking, which decreases absorption of dietary calcium

- A small body frame

- A history of stress fractures, indicating you may already have low bone density

- Vitamin D deficiency, including from limited sunlight exposure

- History of liver disease

- Thyroid disorder

Low-impact fractures often happen in people with osteopenia or osteoporosis, frequently from falls impacting hips, wrists and the spine.

Self-care & Natural Remedies for Bone Health & Osteoporosis

There are many steps you can take at almost any age to help protect your skeletal system against osteoporosis.

- Eat a quality diet including adequate calcium and vitamin D. Aim for a daily minimum of about 800 mg Calcium and 2000 IU of Vitamin D3. Vitamin K2 is helpful as well.

- Exercise by doing weight-bearing activities such as brisk walking, crossfit, hiking, running, weight training, jump rope and brisk dance. Weight training twice a week will build both bone and muscle density and strength. Balance exercise can help prevent falls.

- Consult with a physiotherapist to develop a personalized bone-building recreational exercise routine.

- To help maintain bone strength, quit smoking and decrease alcohol and caffeine intake. Alcohol and caffeine both reduce bone calcification, the process by which bones are hardened.

Statistics

Bone Health and Osteoporosis

Therapy & Treatment for Bone Health & Osteoporosis

If you do not already have a healthcare practitioner who is familiar with identifying and treating symptoms of menopause, the North American Menopause Society provides a list of menopause practitioners here.

A bone density scan is a good idea when entering the menopause transition, if you notice you are losing height or following a bone fracture from a low-impact injury. Bone density, or bone mineral density (BMD), is a measure of how dense bones are relative to the average healthy young woman at peak bone density. It is measured via a DEXA scan (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry), which uses two different, low-radiation X-ray beams to scan mineral content in bone. The result is called a T-score, and it is usually focused on your spine, wrist and hip bones as they are most likely to fracture.

FDA approved medications for osteoporosis fall into two categories. Antiresorptive medications such as bisphosphonates (many brands) and Denosumab protect against further bone loss and may increase bone density. Anabolic medications such as parathyroid hormone (Teriparatide) and Romosozumab rebuild bone and increase bone density.

Hormone therapy (HT) with estrogen is safe and often effective for treating osteopenia and osteoporosis during the menopause transition.

Post-menopause, the selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) drug Raloxifene can reduce osteoporosis and help stabilize bone strength. Raloxifene mimics estrogen’s beneficial effects on bone density in postmenopausal women, with reduced risk relative to HT with estrogen. Users may have hot- flashes as a side effect.

Currently, HT with estrogen can’t be used by some women, including those with breast or ovarian cancer risk, or cardiovascular and stroke risk. Bisphosphonates may pose a risk to those with kidney disease.

There is ongoing research into therapeutic drugs which block Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH) receptor molecules on bone cells or decrease active FSH in circulating blood. Eventually these therapies may also offer help for all individuals with osteopenia or osteoporosis.

The Science

Bone is a living tissue that is constantly remodeling. Cells called osteoblasts are embedded within bone and work at strengthening and reinforcing areas of bone that are under physical stress and strain. They store and secrete calcium and bone matrix proteins.

Meanwhile, other bone cells called osteoclasts remove calcium from the bone matrix and release stored calcium into the blood for purposes such as milk creation for nursing mothers.

Most women reach peak bone mass around age 30. As they age, bone mass, strength and density decrease.

Bone mineral density (BMD) starts decreasing at the start of the menopausal transition, at the same time that FSH starts to rise. This bone breakdown occurs even while the ovaries are secreting estrogen and menstrual periods continue. The loss of bone continues through menopause and postmenopause as shown in the graph.

Estrogen is well understood to build and retain bone by stimulating the specialized cells that grow into bone (called osteoblasts). Estrogen hormone therapy helps retain BMD but it does not seem to reverse osteoporosis significantly. It isn’t known how long HT with estrogen is useful when given past the menopausal transition, since most hormone therapy with estrogen is stopped before a woman is 65, due to changes in cancer risk after this age.

There are many steps you can take at almost any age to help protect your skeletal system against osteoporosis.

- Eat a quality diet including adequate calcium and vitamin D. Aim for a daily minimum of about 800 mg Calcium and 2000 IU of Vitamin D3. Vitamin K2 is helpful as well.

- Exercise by doing weight-bearing activities such as brisk walking, crossfit, hiking, running, weight training, jump rope and brisk dance. Weight training twice a week will build both bone and muscle density and strength. Balance exercise can help prevent falls.

- Consult with a physiotherapist to develop a personalized bone-building recreational exercise routine.

- To help maintain bone strength, quit smoking and decrease alcohol and caffeine intake. Alcohol and caffeine both reduce bone calcification, the process by which bones are hardened.

NO!

Osteoporosis is not a direct symptom of the menopausal transition. However the reduction of estrogen and increase in follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) during the menopausal transition can make osteopenia and osteoporosis worse. Post-menopausal women, and white and Asian women are at particular risk.

Risk factors are listed here

Mystery

Medical research has shown that decreasing estrogen and a steep rise in follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) during menopausal transition contribute to bone loss.

Mystery

New therapies are under development for managing the decline in follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) during the menopausal transition.

FALSE

Many women maintain adequate bone strength throughout their lives. Osteoporosis is a result of many life history factors including genes, puberty, diet, smoking, caffeine intake and physical activity.

Yes, this is a normal symptom.

As estrogen declines during the perimenopausal transition, inflammation in your system develops because estrogen modulates your immune system and the biochemical signals that cause inflammation. You may notice you are developing osteoarthritis in some of your joints, and old joint injuries may begin to hurt and become stiff. As well, some women may experience an increase in their auto-immune disease symptoms.

To date, it isn’t known whether standard HT with estrogen is helpful for joint pain and inflammation. However it is known that joint inflammation can be reduced by regular moderate exercise including modified strength training. Low- impact exercises such as swimming and cycling are excellent at reducing pain and inflammation, promoting high quality sleep and they won’t damage your spine, knees and hips.

You should request a bone density exam by age 65 in order to test for osteoporosis (fragile bones). If you are at risk for low- impact fractures (because of family history) or you have had a low- impact fracture, request this exam by age 50. Low impact fractures commonly occur from falls and result in breaking a wrist or fracturing a vertebrae or hip bone). These types of fractures indicate you may be developing osteoporosis. Losing height by 1.5 inches or more also suggests that you may have some osteoporosis in your spine.

Women who are low-normal or below normal weight, who smoke, drink alcohol, and have low rates of exercise are at higher risk for osteoporosis in post- menopausal life.

Compiled References

1. Bulan, S. E. (2019). Physiology and Pathology of the Female Reproductive Axis. In Melmed, S., Koenig, R., Rosen, C., Auchus, R. & F. Goldfine (Eds.), Williams Textbook of Endocrinology (14th ed., pp. 574-641). Elsevier.

2.Chapurlat, R. D., Garnero, P., Sornay-Rendu, E., et al. (2000). Longitudinal study of bone loss in pre- and perimenopausal women: evidence for bone loss in perimenopausal women. Osteoporosis International, 11(6), 493–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001980070091

3. El Khoudary, S. R., Aggarwal, B., Beckie, T. M., et al. (2020). Menopause Transition and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: Implications for Timing of Early Prevention: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 142(25), e506–e532. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000912

4. Gera, S., Sant, D., Haider, S., et al. (2020). First-in-class humanized FSH blocking antibody targets bone and fat. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(46), 28971–28979. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2014588117

5. Minkin M. J. (2019). Menopause: Hormones, Lifestyle, and Optimizing Aging. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, 46(3), 501–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2019.04.008

6. Santoro, N., Lasley, B., McConnell, D., et al. (2004). Body size and ethnicity are associated with menstrual cycle alterations in women in the early menopausal transition: The Study of Women’s Health across the Nation (SWAN) Daily Hormone Study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 89(6), 2622–2631. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2003-031578

7. Santoro N. (2016). Perimenopause: From Research to Practice. Journal of Women’s Health (2002), 25(4), 332–339. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2015.5556

8. Seifert-Klauss, V., Link, T., Heumann, C., Luppa, P., Haseitl, M., Laakmann, J., Rattenhuber, J., & Kiechle, M. (2006). Influence of pattern of menopausal transition on the amount of trabecular bone loss. Results from a 6-year prospective longitudinal study. Maturitas, 55(4), 317–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.04.024

9. Sowers, M. R., Finkelstein, J. S., Ettinger, B., et al. (2003). The association of endogenous hormone concentrations and bone mineral density measures in pre- and perimenopausal women of four ethnic groups: SWAN. Osteoporosis International, 14(1), 44–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-002-1307-x

10. Sun, L., Peng, Y., Sharrow, A. C., et al. (2006). FSH directly regulates bone mass. Cell, 125(2), 247–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.051

11. Randolph, J. F., Jr, Sowers, M., Gold, et al. (2003). Reproductive hormones in the early menopausal transition: relationship to ethnicity, body size, and menopausal status. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 88(4), 1516–1522. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2002-020777

12. Zaidi, M., Lizneva, D., Kim, S. M., et al. (2018). FSH, Bone Mass, Body Fat, and Biological Aging. Endocrinology, 159(10), 3503–3514. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2018-00601

12. National Institute on Aging. Health Topics: Menopause. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/topics/menopause

13. National Institute on Aging. (2017, June 26). Health Information: Osteoporosis. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/osteoporosis

Original content, last updated February 22, 2023.

© 2025 Herstasis® Health Foundation