Introduction

All women experience changes to their bodies as they age.

You probably remember the first big biological change, marked by the arrival of your first period. This is the only easy-to-identify external sign that you’ve formally entered into reproductive aging, technically termed “menarche”. After that first period, any signs that you are moving into a different life stage are extremely subtle and usually need to be confirmed with lab tests.

We are all growing older every day, but many women don’t realize that medically, there is a reproductive clock that ticks alongside, but not always in sync with, their biological clock (despite the common use of ‘the biological clock’ indicating how much time a woman has left to bear children).

It is this reproductive aging process that determines when you enter into perimenopause, menopause and finally, settle into post-menopausal life.

Menopause can be such a mystery that it is no surprise we don’t even have common language to describe the entire experience. Many of us describe the experience of our changing bodies as ‘starting menopause’. We are equally likely to say we have entered perimenopause.

For the purposes of accuracy, note that menopause is a singular event that is marked when you don’t get a period for a full year.

- Before that, you are in the menopausal transition (or perimenopausal)

- After that you are in postmenopause (or postmenopausal).

Unfortunately for women, information about entering into this tumultuous stage – the menopause transition – is hard to come by. There are physical signs, usually in the form of unpleasant symptoms, that you have entered into the ‘wild ride to menopause’, but no one marker is as easily identified as menarche, or your first period. If you have tracked your periods and know your cycles well, it may be easier to pick up your movement through the stages, but still not guaranteed.

The Reproductive Aging Stages

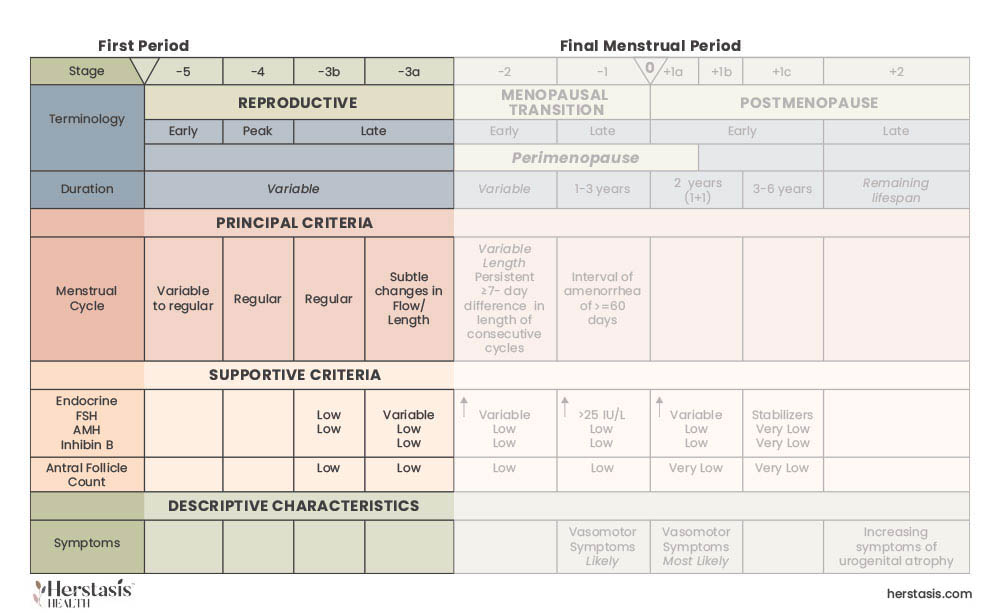

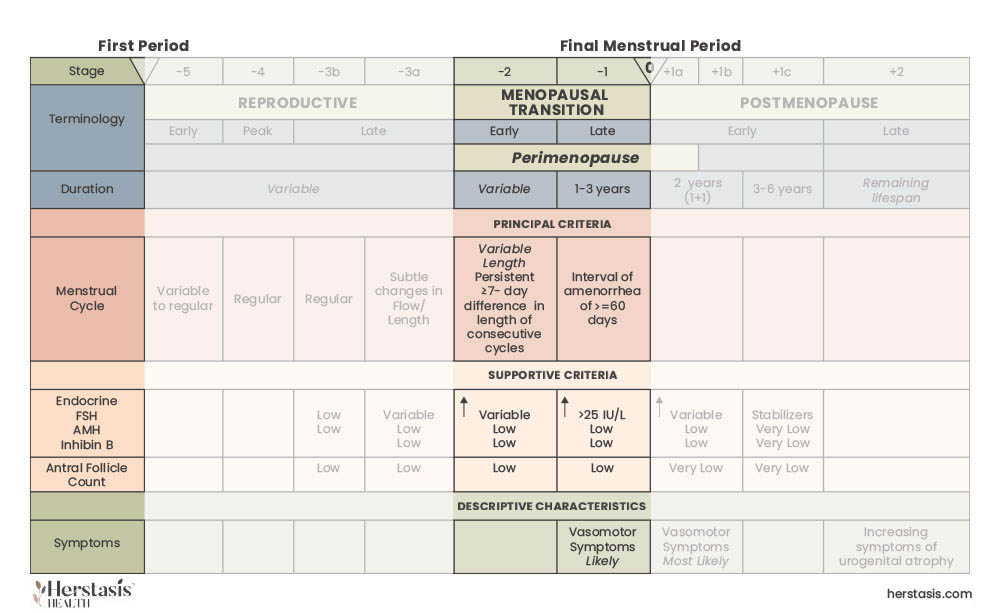

In 2001, a group of experts in women’s health developed a system to formally define the stages of reproductive aging. This work, called the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) was followed in 2012 by the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10 (STRAW+10) which completed the work started in STRAW. The final results from these workshops are shown in the Figure below. [2][3]

A detailed look at stages of female reproductive aging:

Quality of Life During Your Menopause Transition

You can’t control your genetics, which play a large role in menopause, so the age your mother reached menopause is a good predictor of when you may reach it. Your mother’s experiences with menopause (her symptoms etc.) is also a predictor of what you can expect.

You also can’t control some aspects of your environment, butt there are many choices you can control such as getting adequate exercise and good nutrition, and increasing your resilience to stress.

Developing a trusting relationship with your healthcare provider is also important as they serve a critical role in providing information and resources for menopausal care. The North American Menopause Society provides a list of menopause practitioners here.

Unfortunately, some women avoid medical input during their menopausal transition due to a lack of trust in healthcare providers, a lack of access to health care, or personal choices.

These women end up trying to manage their menopausal experiences privately and so miss out on many resources and therapies that are available, lowering their QOL.

If you would like to assess your own Quality of Life, our resources section has several tools available to you. You can also take these QOL questionnaires and provide the results to your healthcare provider for their information.

of perimenopausal women are affected by hot flashes [6]

women over age 50 will break a bone due to osteoporosis [7]

reduction in weekly hot flash frequency with oral estrogen hormone therapy [8]

The Science

The science of the menopausal transition is an active area of research. However, we do know that some reproductive hormones, such as estrogen and progesterone, decline, and that follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) increases, as shown in the graph and described in the text below. [4][5]

What is known is that estrogen is a ‘master regulator’ hormone, impacting virtually every cell in your body. This is why fluctuations in estrogen levels can cause such impactful and diverse symptoms.

Estrogen is important because it is a master regulator of metabolism, brain health, cell division, bone strength, and many other functions in addition to reproduction.[15][16]

Estrogen is a steroid hormone (also called estradiol or E2) secreted by the ovaries and adipose tissue and its’ secretion becomes irregular as early as the Late Reproductive Stage (LRS) (Reproductive: Late Stage) of life. [13] Estrogen may make very dramatic oscillations during the menopausal transition stage, finally steeply declining to close to zero in the last year before menopause. How estrogen variability directly affects short-term symptoms like mood and hot flashes, or chronic conditions like bone thinning (osteopenia and osteoporosis), is not understood. [14]

Progesterone is a steroid hormone, secreted by ovaries with more specialized and fewer known functions than estrogen.[17] Levels of progesterone gradually decrease over the menopause transition before stabilizing at low levels after menopause. [18] [19]

Progesterone mainly functions in fertility and pregnancy. It is secreted by the corpus luteum body of the ovary, triggering changes in the uterus that make it ready to support an implanted fertilized egg. The human placenta also secretes progesterone in support of pregnancy. As well, progesterone is involved in regulating breast tissue growth and differentiation, along with estrogen.

Progesterone may reduce the stiffness of blood vessels, reduce water retention in the body, and modulate the sleep regulating hormone melatonin. [20] Consequently, the gradual loss of progesterone during menopausal transition may increase water retention and affect sleep quality.

During the late reproductive stage (Reproductive: Late Stage), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), oscillates in sync with your other reproductive hormones. FSH triggers oocyte (egg cell) maturation and release and stimulates the secretion of estrogen from the ovary.

During the early menopausal transition (Reproductive: Early & Peak Stage) , FSH rises steeply to high levels. FSH levels plateau near the end of the menopausal transition and persists at this level post-menopause. [22][23][24] High levels of FSH, along with declining estrogen, may affect bone health and increase the likelihood of obesity. [25]

Blood glucose levels may become dysregulated and variable during menopausal transition, possibly due to irregular and declining estrogen and rising FSH. Brain glucose dysregulation may contribute to memory and concentration challenges seen during the menopause transition. [26]

What does this mean for me?

Knowledge is power, and personal knowledge is even more powerful. Most women are frustrated during the menopause transition because they can’t get clear answers about what is happening in their own bodies. Some may be experiencing debilitating symptoms. Others may want to understand possible therapies and the implications of those therapies. Many women just need to be heard and reassured that what they are experiencing is normal, that they aren’t “crazy” or “dying”. They want to understand what symptoms are transient versus what ones are permanent.

The current medical system has not prioritized mid-life women’s health, but this is starting to change. This lack of abundant resources for women nearing or in their menopause transition is the driving force behind what we are doing at Herstasis.

Remember – it is possible to have a healthy menopause with personal perspective and a sense of control! And we’ll be with you every step of the way.

MYTH

This myth is rooted in ageist and sexist attitudes. Most women in menopausal transition are healthy, happy and productive. Women cope with their symptoms like they cope with most other challenges in life – adequately at worst and successfully at best.

MYSTERY

Generally estrogen and progesterone levels decline and FHS (follicle-stimulating hormone) levels increase, all stabilizing at new levels following menopause. Changes in hormone levels are highly variable from woman to woman, and currently there is little data (and no easy way to collect data) about the individual woman’s reproductive hormone levels on a day-to-day, and month-to month, basis during menopausal transition. Other important hormones and neurotransmitter levels are not known either.[27]

MYSTERY

Since hormone levels can’t be accurately tracked day-to-day/ month-to-month for individual women, the impact of hormones on symptoms is speculative for most symptoms. Technological tracking of symptoms and biomarkers over time is lacking. The result is that current research can only correlate changing hormones with symptoms for averaged populations of women, and with only a rough idea of timing of these events.

MYSTERY

There aren’t solid answers but the ideas from anthropology, genetics and evolution give some interesting hypotheses. Here are two of them:

1 “Why do women outlive their fertility?”

Twenty-first century women (and people in general) are living 40- 50 years longer than women did before 1900. At that time, most women died around age 40 (across different cultures), before even reaching the menopausal transition. Living through the menopausal transition and beyond is relatively recent.

There may be no evolutionary “purpose”, or survival advantage, to either individual women or to their descendants. The length of the reproductive life span in human females is comparable to other great apes, however great apes die soon after their reproductive systems age and stop functioning. The hypothesis is that menopause might not be the key trait. Perhaps the ability to extend life post-menopause is the critical trait that needs more attention. [28]

2 “The Grandmother Hypothesis”

Overwhelmingly, women of past generations had children at a younger age than now, typically starting in their teens and early 20’s. After children are born to a young woman and her family, her genetic contribution to future generations is complete. Since childhood disease and trauma impact human mortality so strongly, children’s survival becomes evolutionarily paramount. When women have children that survive long enough to bear them grandchildren, the continuation of the woman’s genes becomes more probable. As well, grandmothers may improve the likelihood of her grandchildren’s survival by sharing her resources, help and knowledge, creating more insurance for the survival of her genes. This hypothesis is called “Kin Selection” and it proposes that there are strong natural selection factors supporting longer lifespans (for both women and men). [29][30]

[1] Baker FC, de Zambotti M, Colrain IM, Bei B. Sleep problems during the menopausal transition: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Nat Sci Sleep. 2018;10:73-95 https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S125807

[2] Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, Rebar R, Santoro N, Utian W, Woods N. Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW). J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001 Nov;10(9):843-8. doi: 10.1089/152460901753285732. PMID: 11747678.

[3] Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, Lobo R, Maki P, Rebar RW, Sherman S, Sluss PM, de Villiers TJ; STRAW+10 Collaborative Group. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop +10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Climacteric. 2012 Apr;15(2):105-14. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2011.650656. Epub 2012 Feb 16. PMID: 22338612; PMCID: PMC3580996.

[4] Randolph JF, Jr, Zheng H, Sowers MR, et al. Change in follicle-stimulating hormone and estradiol across the menopausal transition: effect of age at the final menstrual period. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:746–754.

[5] Randolph JF, Jr, Sowers M, Bondarenko IV, Harlow SD, Luborsky JL, Little RJ. Change in estradiol and follicle-stimulating hormone across the early menopausal transition: effects of ethnicity and age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1555–1561.

[6] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539827/

[7] https://www.nof.org/preventing-fractures/general-facts/what-women-need-to-know/

[8] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7004247/

Original content, last updated February 17, 2025.

© 2025 Herstasis® Health Foundation

![The female reproductive clock - the three stages of your reproductive age and corresponding hormone levels. [1]](https://www.herstasis.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Three-Stages-768x593.jpg)